The Sedimentary Mind

When I was a child, I walked with my father along the gentle crests and furrows of the hilltop farm where he was raised. Grandmother, too, would lead adventures into the far pastures, often with some specific bounty in mind. We might stain our hands fuchsia picking elderberries for afternoon tea, or return with a bucket of sweet, gooey persimmons fallen after first frost. In the evenings, we feasted on our spoils as paparazzi fireflies sizzled against a chorus of bullfrogs and whip-poor-wills. As August’s ceiling of stars rotated into full view, I would slip into the angular shadow cast by the barn and watch the Perseids slice the Milky Way wide open.

Even after daybreak wrestled away the night, some remnant of the darkness always persisted, slinking into a cave folded within the farm’s western flank. The cavern is small with jointed, jagged walls, and is often filled by the musty odor of sulfur percolating out of the stone through each burrowing raindrop. My father remembers a second, larger chamber from his childhood, though it is impossible to know whether its disappearance is the product of settling earth or shifting memory.

Imprinted into the strata from which the cave was carved, the voice of an ancient Mississippian wind slumbers. These winds sailed across an inland sea, churning the water, and scouring rippled footprints in the sandy bottom. Now the undulating surface of the Black Hand sandstone is overlain by roots and Roundup. Gargantuan blocks occasionally tumble out of the hillsides, calving as the softer shales erode beneath. These reclined slabs provide an ideal vantage point to lie back and take inventory of the heavens. Looking up, cushiony cumulus drifters wander across a great blue expanse. It is an impressionistic, chicory blossom blue, the same hue which is painted in broad swaths across maps of Carboniferous Ohio. Closing both eyes for a moment, I focus on the stone crests kissing my neck and imagine myself beneath all that blue, subject to the whims of the waves scribbling across the ocean floor.

There are many other forms cast in the rock besides ripples. Traces of burrowing, crawling, sweeping, and dragging all appear, though the perpetrators of these events remain elusive. In much the same way, the tones and textures of objects I’ve encountered leave behind impressions in the sedimented assemblage of my experiences. Regardless of the distance I dispatch, these shapes remain rooted: woolly salsify manes jettisoned by a breath, sloughing fall bark of the sycamores underfoot, and blackberry brambles drawing blood. These objects establish the the borders of the farm in my memory. Likewise, certain boulders, branches, brooks mark the extents of the farm on paper, in the form of a warranty deed.

There is a long tradition of prosaic cartography, in which one’s claim upon a place is essentially the story of their journey through it. The surveying scheme of “metes and bounds” codified this narrative system into law, demarcating parcel rights by virtue of towering trunks and robust boulders. These natural landmarks were bounds, anchoring those circumscribed within their perimeter to the loamy soils, and conjuring identity from footfalls.

Rebecca Solnit’s A Field Guide for Getting Lost describes how “the landscape in which identity is supposed to be grounded is not solid stuff; it’s made of memory and desire…Thus place, which is always spoken of as though it only counts when you’re present, possesses you in its absence…It is as though in the way places stay with you and that you long for them they become deities…they are what you can possess and in the end what possesses you.” Deities, both benign and malevolent, arise when the fabrics of moments-experienced and terrain-traversed become irrevocably interwoven.

Solnit’s deified places “superimpose coordinates from two different kinds of space”, to borrow a phrase from Matthew Battles. On one hand, there is the hierarchical logic of cartography: parcels within counties within provinces, positions fixed by longitude and latitude. Intersecting this plane is a geographic dimension evoked emotionally, with location rendered through recollections and feelings. These planes are bolted together by bounding objects to form a multidimensional slide rule gauging one’s own history; an instrument calibrated specifically to the individual whose identity it describes.

In an essay subtitled How things in the world become sacred in a museum, Battles, former preparator for Chicago’s Field Museum, muses about all that is embodied within bounding objects. “The word ‘habit’ catches for me a sense of the shoddy assortment of qualities that knits an object into the fabric of things, weaving into one whole its social roles, the cultural codes it keys, and its whence-and-whither entanglements with deep time.” However, while still enmeshed within their contexts, these entanglements prove difficult to tease apart, and it falls upon the examiner to prepare, or “re-raw”, the objects. This pursuit is necessary because, “The stories they tell, the truths they were meant to exhibit and enact, are nowhere self-evident.”

Can the person also be “re-rawed”? Peering out from Chicago’s lakefront in 1953, Aaron Siskind began photographing airborne divers in a series titled Pleasures and Terrors of Levitation. The twisting bodies of the young men appear to have been momentarily forsaken by Newton’s laws; immobilized meteors hanging, isolated against a brilliant barren sky. Siskind produced these airless images over the course of several decades, each one containing a single motionless figure immersed not in Lake Michigan, but instead in the void.

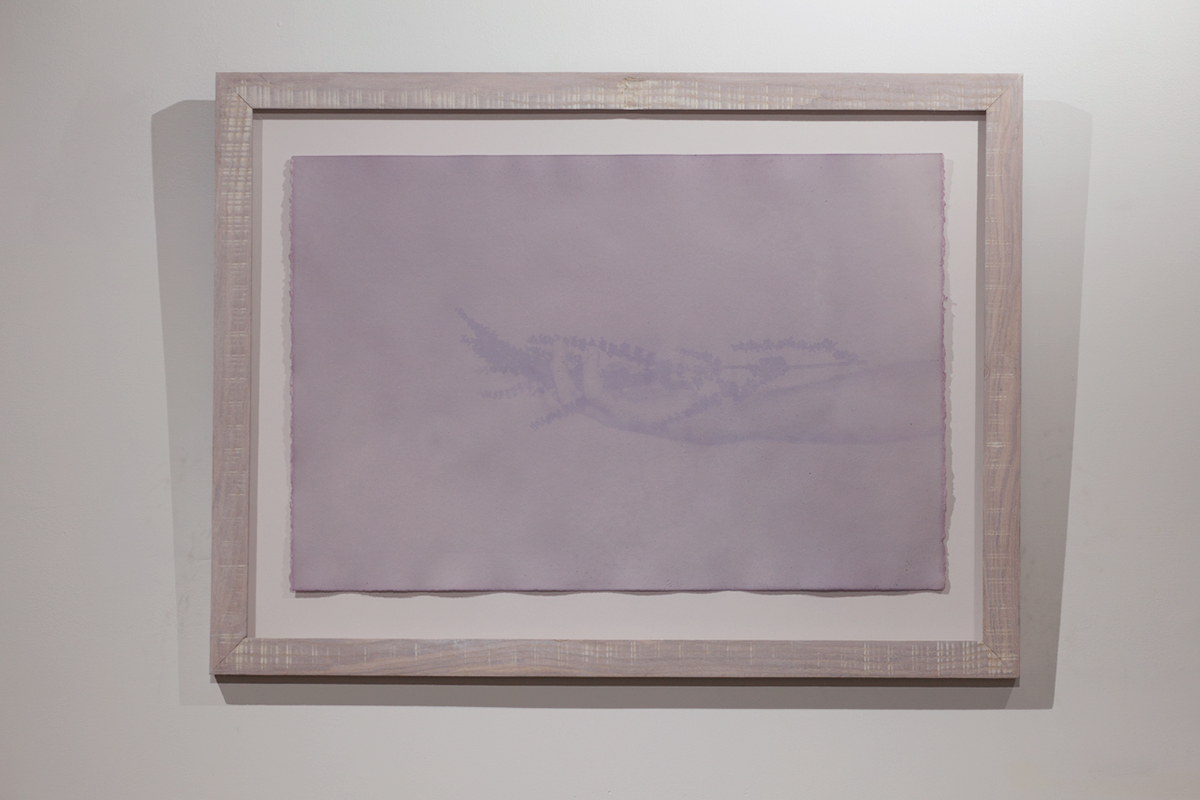

Pleasures echoes the pristine botanical photographs published by Karl Blossfeldt a quarter-century earlier. Claimed by history as the paradigmatic New Objectivity photographer, Blossfeldt’s crisp enlargements eschewed narrative, context, and dimensional pictorial space. Weimar-era art critic Franz Roh characterized the New Objectivity as “Magical Realism”, writing that “The new idea of ‘realistic depiction’…is not to portray or copy but rather to build rigorously, to construct objects that exist in the world in their particular primordial shape.” In order to find this primordial shape, or habit-made-visible, an observer must devise some mechanism by which to extricate the object from its entanglements. Philosopher-essayist Walter Benjamin championed Blossfeldt’s accomplishment, writing that “Details of structure…are more native to the camera than the atmospheric landscape or the soulful portrait. Yet at the same time, photography reveals in this material…image worlds, which dwell in the smallest things – meaningful yet covert enough to find a hiding place in waking dreams.”

Siskind once quipped that “the only nature that interests me is my own.” This could reasonably be understood to mean something internal and governing (e.g. human nature), or, alternatively, it could refer to something encountered and claimed (e.g. a niche in the environment). Specimens flourishes amidst this ambiguous syntax and explores a third interpretation derived from the intersection of the two alternative readings: objects observed outwardly resonate with identity felt inwardly, a person’s nature is equal parts internal and external, and the experience of a place bestows some particular species of ownership. Taking up the New Objectivity’s scalpel of unflinching observation, Specimens attempts to isolate and identify the unseen relationship between person and place.